|

Since

the Seventeen-hundreds, from Italy to Northern Europe, traveling organ grinders

filled a specific role in social relations, literature, politics, and music.

They spread the news among the populace, often in Moritaten, irreverent songs

that were sometimes based on familiar melodies. Like the "yellow press" of

today, the organ grinders entertained and reported on scandals, sex and crime,

usually unauthorized by the authorities. They provided entertainment, by

popularizing simple melodies in their first form of reproducible mass-media. In

the 19th century, as literacy rates increased, news, romance, and adventure

tales were carried by the penny press, but the organ grinder remained a popular

form of "low" entertainment for the working class. Since

the Seventeen-hundreds, from Italy to Northern Europe, traveling organ grinders

filled a specific role in social relations, literature, politics, and music.

They spread the news among the populace, often in Moritaten, irreverent songs

that were sometimes based on familiar melodies. Like the "yellow press" of

today, the organ grinders entertained and reported on scandals, sex and crime,

usually unauthorized by the authorities. They provided entertainment, by

popularizing simple melodies in their first form of reproducible mass-media. In

the 19th century, as literacy rates increased, news, romance, and adventure

tales were carried by the penny press, but the organ grinder remained a popular

form of "low" entertainment for the working class.

Domestic workers,

factory workers who lived in harsh conditions, often far from home, cherished

the melodies and stories, which often depicted the fates of people like

themselves: jilted sweethearts, single mothers, homesick migrants. They enjoyed

hearing and singing along to songs of fantastic adventures of pirates, robbers,

warriors, and other outlaws. Narrative ballads like "Frankie and Johnnie",

"Mack, the Knife", or singing the Blues are a continuation of these

storytelling songs.

Of course, newer

forms of mass media and entertainment emerged in the 20th century, namely

radio, television, and, most recently, the Internet. On a technical level,

mechanical organs, which reproduce pre-recorded data, can be seen as early

applied forms and catalysts in the invention of new technology to store and

reproduce information.

Mechanical crank

organs have been built in Europe for over 200 years. However, organs are much

older than that. An organ mechanism that could be activated by hand, has been

documented as far back as the third century BC, an invention attributed to

Ctesibios of

Alexandria (285 - 222 BC) who discovered and applied the powers of

pneumatics. Another early description of a mechanical music instrument goes

back to Confucius, who describes in his work, "The Chinese Nightingale" an

organ-like instrument that could imitate such bird sounds.

The crank organ made

it possible to make music mechanically, to store the melodies, and to repeat

their performance many times over. Previously, only the mechanical clock or a

music box could do that.

The

oldest existing cylinders that were used to record musical information

mechanically date back to a music automat made in Augsburg, Germany, from the

year 1600. Later, Emperor Frederick the Great (1740-1786) carried out an

unprecedented technological innovation initiative by inviting scientists,

thinkers, and craftsmen from all over Europe to settle in Prussia. He supported

no less than twenty-four music-box makers, whose task it was to build

sophisticated clocks with organ works, so-called music-boxes. As a sideline,

they developed crank organs. The first manufactures for crank organs date back

to the 1790's. The

oldest existing cylinders that were used to record musical information

mechanically date back to a music automat made in Augsburg, Germany, from the

year 1600. Later, Emperor Frederick the Great (1740-1786) carried out an

unprecedented technological innovation initiative by inviting scientists,

thinkers, and craftsmen from all over Europe to settle in Prussia. He supported

no less than twenty-four music-box makers, whose task it was to build

sophisticated clocks with organ works, so-called music-boxes. As a sideline,

they developed crank organs. The first manufactures for crank organs date back

to the 1790's.

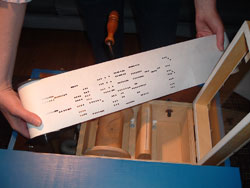

A mechanical organ

has three main components: the organ works with pipes and bellows, the play

action, and the exchangeable cylinders made of wood and/or metal that carried

the individual tunes. After the invention of the mechanical weaving loom,

folding punch cartons were developed to carry the music data, increasing the

repertoire more easily and cheaply; successively, hole-punched tapes or

paper-strips served as information carriers for the music. The newest

information carriers are microchips, which have become part of some crank

organs that are being built today. A mechanical organ

has three main components: the organ works with pipes and bellows, the play

action, and the exchangeable cylinders made of wood and/or metal that carried

the individual tunes. After the invention of the mechanical weaving loom,

folding punch cartons were developed to carry the music data, increasing the

repertoire more easily and cheaply; successively, hole-punched tapes or

paper-strips served as information carriers for the music. The newest

information carriers are microchips, which have become part of some crank

organs that are being built today.

Although technology

has made tremendous leaps, the basic principle of the crank organ remains the

same. It is a portable, mechanical music instrument, which has enough volume to

be heard on the street as well as indoors, without further electric

amplification.

Composers like

Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven were not above writing melodies for "flute-clocks"

and other mechanical music works. They realized the potential of crank organs

as a first form of "mass media". The lowly organ grinder disseminated and

popularized their music among the public. Many of these melodies were sung and

whistled to, and became literally hits on the street.

Organ grinders had to

play for pennies, traveling form town to town, from market place to market

place, not to overstay their welcome. Especially in Italy, it was not uncommon

for a "patron" to adopt a child from a poor family, promising to give the child

work north of the Alps, and relieving the destitute family of one more mouth to

feed. Unfortunately, these children continued to lead a hard life: some were

trained as fiddlers or acrobats, but just as often as pickpockets, petty

criminals, and child prostitutes, beholden to their master. Maybe the least

talented ones were sent on the street to work as organ grinders?

Historically, organ

grinders were in the same social group as peddlers, ragmen, circus folk, just

above tinkers and gypsies. One of the most touching descriptions of a poor

organ grinder is in the last song of Robert Schumann's

"Winterreise",

Der Leiermann, a haunting and beautiful song cycle. Throughout the 19th

century, they were denied the limited civil rights that town residents might

have enjoyed: they were barred from many trades, from settling in town, from

owning property. But they also held a fascination for their listeners, and the

mystery of more freedom and of the courage to say things that were irreverent,

even dangerous. The playwright, Bertold Brecht, and composer Kurt Weill open

their "Threepenny Opera" with such an edgy organ grinder piece about the

underworld crime boss, MacHeath.

As industrialization

gave rise to the big cities with their large tenements and countless workers

migrating to their factories, the organ grinder was a common sight,

playing in the back alleys

of the tenements. Children, laborers, and domestic workers loved the

strains coming from the organ, and soon sang along with new and old familiar

melodies, not forgetting to

compensate the entertainer

for his labors.

Today, crank organs

have become a rarity; the street singer, belting Moritaten alongside, even more

so. Carrying on such an old folk art, is truly unique and worth cherishing, and

may give new life to this old popular art form.

Home | Bios | Music |

Performances |

History |

Photos |

Contact

|